Blogs

Magnetic Movements

Exploring the Relational and Performative Potential of Smart Materials | By Pascalle Paumen

On September 26, 2024, I attended the workshop “Expressive Mechanisms: From Petri-dish to Performativity” which took place at the Innovation:Lab at Theater Utrecht. The workshop was organised by 4TU.Design United, coordinated by Amy Winters from TU/e, and involved researchers of the Dramaturgy for Devices project to encounter soft robotic technologies. Soft robotics show great potential for applications such as targeted drug delivery in biomedicine, but currently often remains confined to labs or maker spaces and lacks broader socio-cultural relevance. In the workshop we considered these technologies in a theatre context, viewing them not as mere functional tools but instead exploring how they may play a role in social encounters. Our approach was guided by the notion of designing with encounters (Gemeinboeck, 2021) which takes actual encounters between humans and machines as starting points for developing HRI, rather than designing robots as agents with pre-defined behaviours. Our aim was to experiment with the materials and reflect on them as relational and performative participants in creating novel interactions.

Smart magnetic materials

We first received a showcase of smart magnetic materials by Venkat Venkiteswaran, assistant professor in biomechanical engineering at the University of Twente. These materials were magnetic actuator props, which allow objects to move and transform through invisible magnetic forces and thereby engage in dynamic behaviours (Venkiteswaran et al., 2020). Swaying a tool underneath a sample on plexiglass, he demonstrated a handful of reactive materials which moved as a result of the repetitive motions. The demonstration raised some questions for us as we anticipated the next stages of our workshop: How controllable are the materials? What are their various affordances and how will they affect our interactions, both with the materials and each other?

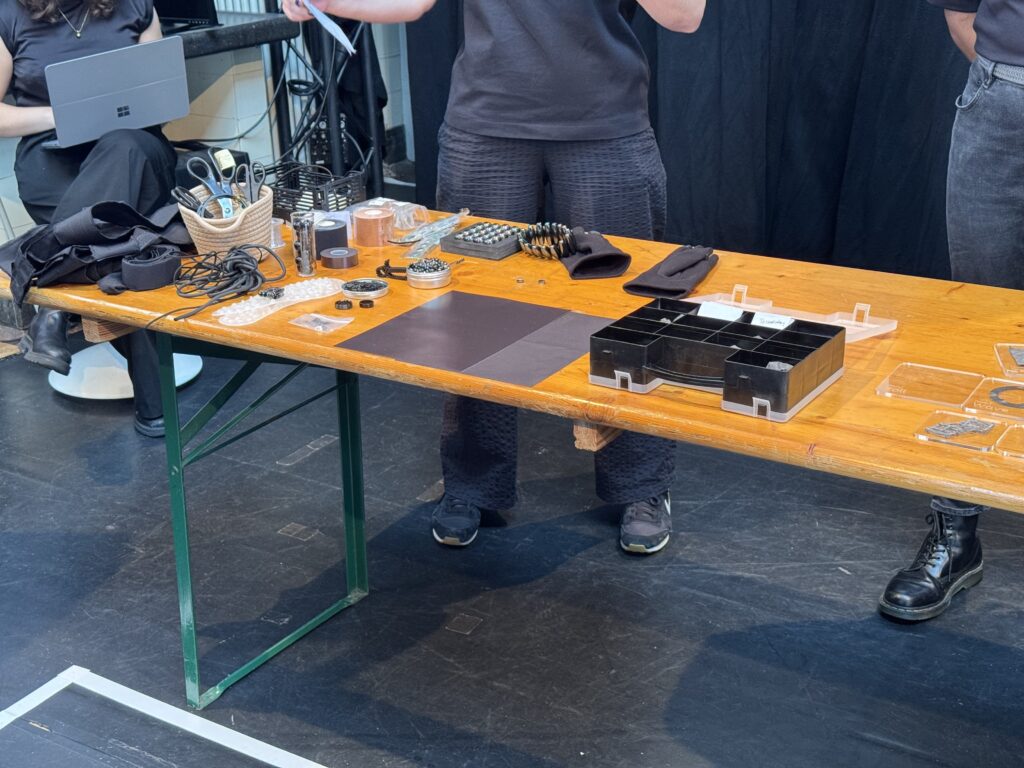

In the next stages, we began to unravel first insights into these and more questions. At a large table with more samples, we were invited to now confront these materials ourselves by playing and experimenting with them. My first attempt was trying to move the materials laid on top of plexiglass without touching them, only using magnetic force. In these initial minutes, everyone was noticably careful in picking up the items, worried about accidentally damaging them. We needed to get a feeling for how robust the materials were, how they would react to us and our movements.

‘The spine’

Things quickly took a turn when one of the PhD candidates, Anita Vrins, asked for help in creating what would later be referred to as ‘the spine’. Her task description: “Turn me into a dinosaur”. I grabbed some of the velcro tape and placed it vertically along her spine. Soyun Jang, Nefeli Kousi, and Enne Lampe – the remaining PhDs – joined in and helped tape magnets on her back. Finally, we took magnetic cloths and tried placing them on her spine in such a way that they would resemble stegosaurus spikes. This was more difficult than anticipated, as the cloth would not stay in the shape we wanted. Attempts at ‘spine surgery’ were made by merging multiple cloths, or keeping them lifted by hovering magnets above. Once the possibility of merging bodies with materials had formed, more constructions followed: Enne’s ‘pirate’, consisting of a cloth earring and one material acting as a parrot; or ‘the veil’, in which we placed cloths on Soyun’s forehead. In ‘the dance’, Anita and I tried sharing the cloths from one body part to another, sometimes holding onto each other for balance. All these experiments required us to collaborate and participate in intimate encounters with each other and with these difficult-to-control materials.

Connection & Interaction

After a lunch break, it was time to dive deeper into ideas that had emerged from our explorations. We did so through speculative enactment, where some participants acted out scenarios. First, Enne and Nefeli performed encounters where they placed materials on their shoulders which acted as companions. It became apparent that in these scenes, a lot of imagination was needed to make the items ‘become’ something creature-like. Project leader Maaike Bleeker noted that the focus was too much on creating a narrative, rather than exploring how the materials themselves could give rise to connection and interaction. Following this intervention, things changed when Soyun and Enne performed together, collaborating in using big magnets to manipulate magnetic cloth. Their focus was on the material and how they could work together in bringing about different movements. This created a mutual investment in sustaining the relationship, which could only work through connecting with each other and engaging in a balancing act. Things came full circle in Nefeli’s following solo performance, where she put on ‘the veil’ and focused on the properties of the magnetic cloth. Exploring the material on her forehead, she realised that the cloths could be braided together and thus created a sort of ‘flower crown’. Afterwards reflecting on her experience, she said: “from one ability it built up into a whole area of possibilities”.

Not imposing meaning on matter and instead engaging in play and enactment steered us towards discovering the unique qualities of these particular materials, and thus generated possibilities like braiding cloths. Meaning was negotiated in the situated encounter between humans and materials, instead of being ascribed to the robot based on its appearance or an imagined narrative (as was the case in our initial speculative enactments). As Gemeinboeck and Saunders (2022) put it, this “frees the machine communicator to become its own ‘thing’; a more or less social, unique artefact, depending on both its machinelike abilities to participate in this negotiation and the relational affordances of the unfolding situation” (p. 556). Design approaches such as these hence open up new possibilities for developing robots capable of sustainable interactions, as they lead to better understanding of robots’ agency and sociality, and take into account that human-robot interactions will take place in situated, embodied contexts. As we study how to effectively bring about sustained relationships with robots, theatre serves as an excellent forum for exploring how robots can be designed to adapt and engage in more dynamic interactions. Working with these materials ultimately contributed to our Dramaturgy for Devices project by allowing our PhD candidates to gain hands-on experience with what it means to design with encounters – insights which serve as a fruitful kick-off for their various individual projects.

References

Gemeinboeck, P. (2021). The Aesthetics of Encounter: A Relational-Performative Design Approach to Human-Robot Interaction. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 7, 577900. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2020.577900

Gemeinboeck, P., & Saunders, R. (2022). Moving beyond the mirror: Relational and performative meaning making in human–robot communication. AI & SOCIETY, 37(2), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01212-1

Venkiteswaran, V. K., Tan, D. K., & Misra, S. (2020). Tandem actuation of legged locomotion and grasping manipulation in soft robots using magnetic fields. Extreme Mechanics Letters, 41, 101023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eml.2020.101023