Blogs

Rober in the Room

Designing Human-Robot Encounters for the CTRL + ALT + PLAY event | By Pascalle Paumen

From November 28 to November 30, 2024, researchers of the Dramaturgy for Devices project gathered in Utrecht for a second joint workshop to experiment with human-robot interactions. This time, we explored designing with and for encounters using the Rober robot – a table-like serving robot for the hospitality industry created by Dalco Robotics. During the first two days at the Parnassos Cultuurcentrum, we tried out various ways of moving and engaging (with) Rober in a space. On November 30, we then tested our ideas ‘in the wild’ at the CTRL + ALT + PLAY event at Theater Utrecht, hosted by the Innovation:Lab.

Day 1: Experimenting with Movements

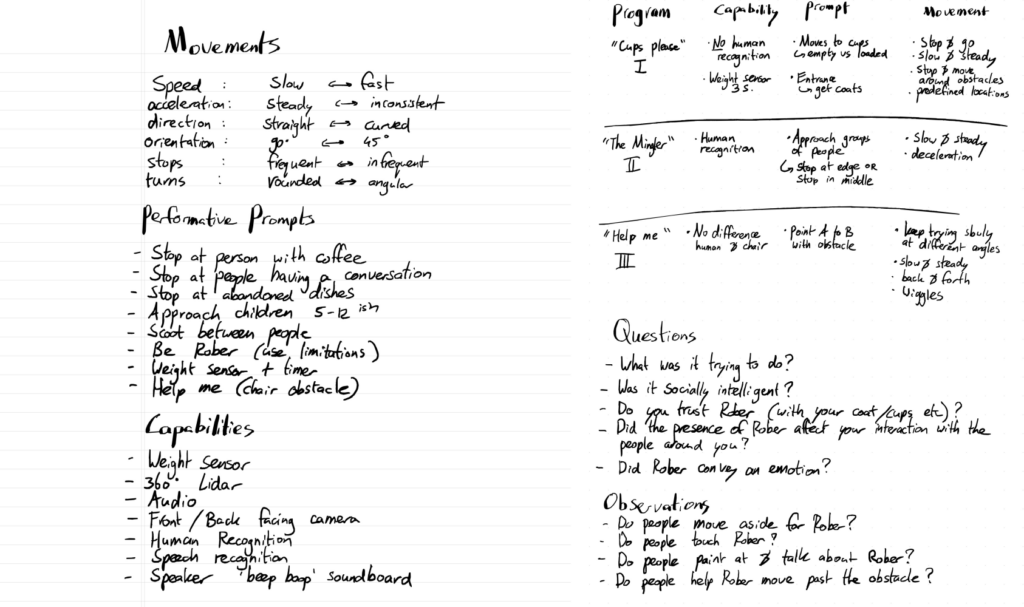

In our workshop we wanted to experiment with Rober’s various movements and what interactions they may invite. As such, on the first day we tried out various encounters, each of us coming up with a different (narrative) prompt, desired interaction, or movement for Rober. First, we changed Rober’s intended purpose – carrying dishes – to carrying jackets. The jackets were placed on the floor against a wall, while one of our researchers (Marco Rozendaal) controlled Rober through a handheld console. Navigating Rober towards the jackets, it was evident that the robot could not pick up anything by itself and would need assistance. Marco therefore let Rober move in repetitive back-and-forth motions towards the jackets to indicate a struggle, then directed attention to me – by turning the robot to me and moving towards me and back to the jackets – to let Rober ‘ask’ for help. I picked up the jackets, felt inclined to wave and say hi to Rober, and put them on the top tray. The robot felt quite creature-like in this encounter, like a cat asking for help to open a door.

In a second encounter, we positioned ourselves as people moving in the space and minding our own business, as Rober would try to move past us. Here we tried out two speeds: higher speed versus slower, more constant movement towards us. The accelerated speed felt quite threatening as Rober would charge at us, pushing us out of the way like a person might. The slower speed, at a constant pace, changed our perception of Rober to that of a polite service robot which was part of the scenery: it invited us to step away in a way that almost felt non-negotiable.

In our last experiments of the day, we divided into two groups each creating two scenarios. The first scenarios of group one had us moving around in the space without further instruction, with the robot moving around us continuously either with us or avoiding us. The others had us in an art museum with a catering space, instructing us to move around as visitors. Rober here was variedly a kitchen aid – a function which felt natural – and a security guard, which was misinterpreted as Rober actually posing a threat to the ‘artworks’. These latter experiments were insightful in that they helped us understand meaning as not inherent to specific movements – rather, we made sense and attributed meaning to Rober’s motions based on the situated contexts the movements took place in.

Day 2: Polishing Performative Prompts

On the second day, we had a presentation by Irene Alcubilla Troughton, Assistant Professor in Performance and Technology at Utrecht University who recently completed her PhD dissertation. She presented part of her work on a performing arts approach to relational HRI design, introducing us to a relational framework for movement (for more information, see her upcoming PhD defence). In her work with bottom-up, exploratory workshops with robots, we found connections to our own practice: Patterns like “stuck and help”, where Rober would seem stuck and which would serve as a stimulus for a human’s helping action.

Following this inspiring talk, our PhD researchers – Enne Lampe, Anita Vrins, Soyun Jang, and Nefeli Kousi – and I finalised our plan for the following day, on which we would let Rober loose in the foyer of the CTRL + ALT + PLAY event. After exploring Rober’s possible movements (and finding a shared language for them) and its real or imagined capabilities, we came up with three programs. In “Cups please”, Rober would first collect jackets before moving on to collecting empty cups. “The Mingler” would have it approaching groups of people and trying to socialize. Lastly, “Help me” would bring us full circle to the first experiment, having Rober struggling with some obstacle and requiring human assistance.

Day 3: A Robot in the Wild

On November 30, it was finally time to let Rober loose. As visitors explored the various exhibitions at the event, our robot began moving – with empty trays – out of the wardrobe where it had been stored. As it moved towards and in-between a group, people took brief notice before stepping around it and continuing their conversation. A woman, as Rober moved towards her, spread out her arms in a hug-like gesture, then motioned it towards her with her hands.

Having infiltrated the foyer, it was time for Rober to engage in its first program. Soyun began instructing people to put their jackets on Rober, sparking questions like “Does it feel weight?” People bent down to take closer looks at the robot, engaging in various different interactions: mimicking to kick it; waving at it; petting it. Some put their coats on it, while others do not pay attention to Rober’s invitation through its back-and-forth movements. In the wardrobe itself, Rober becomes an obstacle for hanging up coats, and is in need of human aid. A man comments: “It’s typical automation stuff (…) I feel like I’m going through more trouble rather than less”.

When someone put an empty glass on Rober unprompted, we switched to using Rober as an empty glass collector. Visitors picked up this function fast, as it seemed to be Rober’s most ‘natural’ purpose based on its affordances and design. One of the waitresses began guiding Rober through the space, blocking it with her body or walking slowly behind it while pointing in certain directions. After putting empty dishes on it, she would motion thank-you at the robot. We noticed that Rober now drew less attention from surrounding people as it had become part of the environment, and the repetition of collecting dishes had built an understanding of Rober’s purpose.

Testing some “Help please” encounters – after getting a scarf from someone – Rober ‘escaped’ through a door, then moved back-and-forth in front of the now-closed door until a child opened it. In another encounter, Rober moved towards a table with empty cups, but the seated person thought it was malfunctioning, jumped up and forcefully redirected the robot away from the table. When situated outside a closed door, the back-and-forth movements were understood – yet when ‘asking’ for empty dishes, the same movement was not always an obvious sign.

In “Mingler” mode, we had Rober bumping into a man who was engaged in another exhibit, then following the man around and playfully bumping into him. Here, it received a “crew/artist” badge with which it drove off. As Rober became more erratic and disruptive in its movements, people no longer put cups on it. While some people were willing to play, Rober sometimes caused awkwardness and frustration when pushing itself between people engaged in in conversations.

Reflections

Reflecting upon our experiences, we noted how much Rober could blend in when acting as a cup bearer, while it had great disruptive potential in other modes. Its function as a waiter had people chasing it out of a pragmatic need, while there was annoyance when it mingled. People engaged in a lot of verbal and body languages to instruct or ‘control’ Rober, and we were surprised about the ease with which we had people assume Rober’s autonomy, when in reality we controlled all its movements. As a possible avenue for further inquiry, we wondered about the various factors influencing whether people would accept or reject Rober’s invitations – whether to play or put things on it – and how different contexts would influence the meaning-making process of the robot.